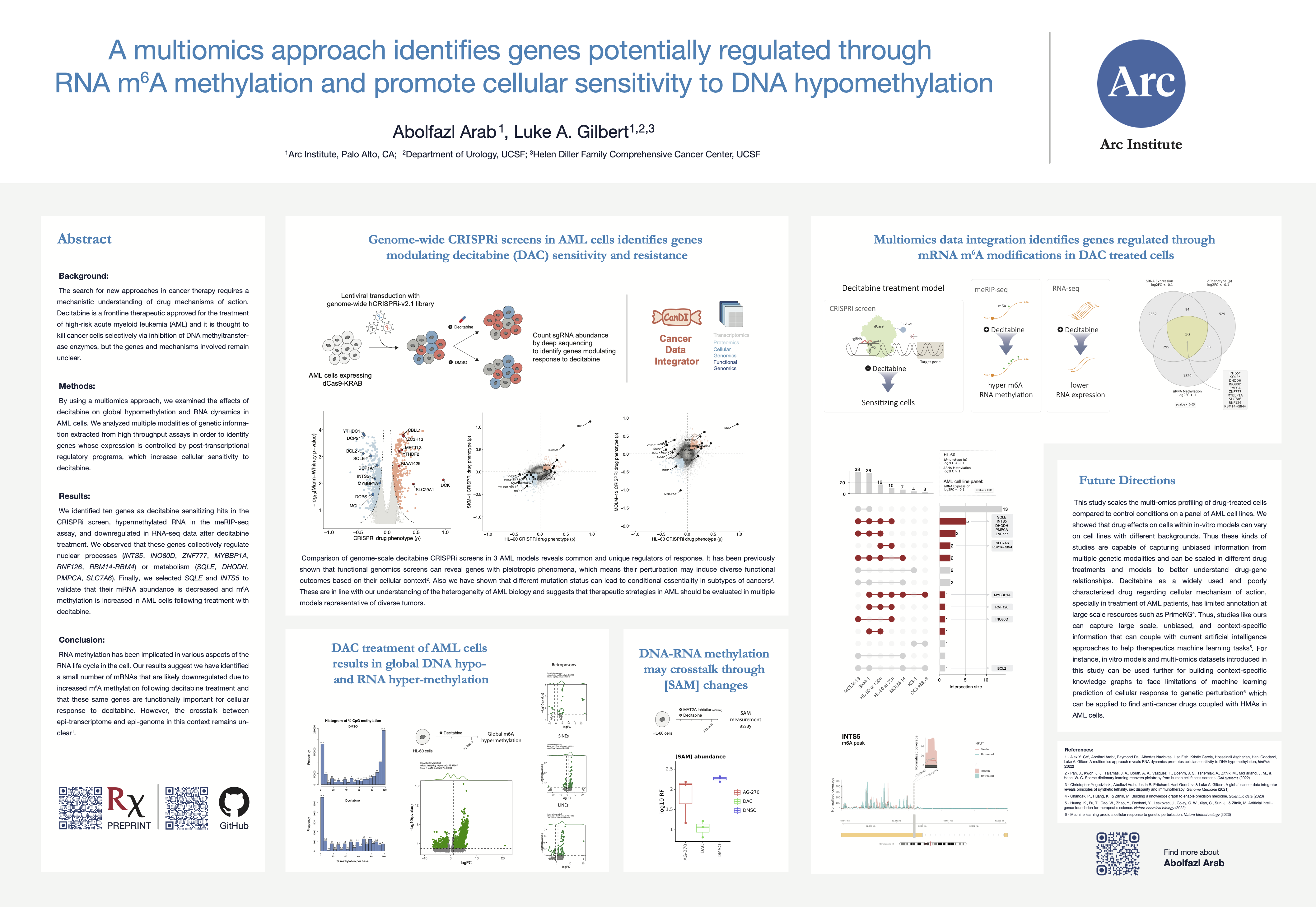

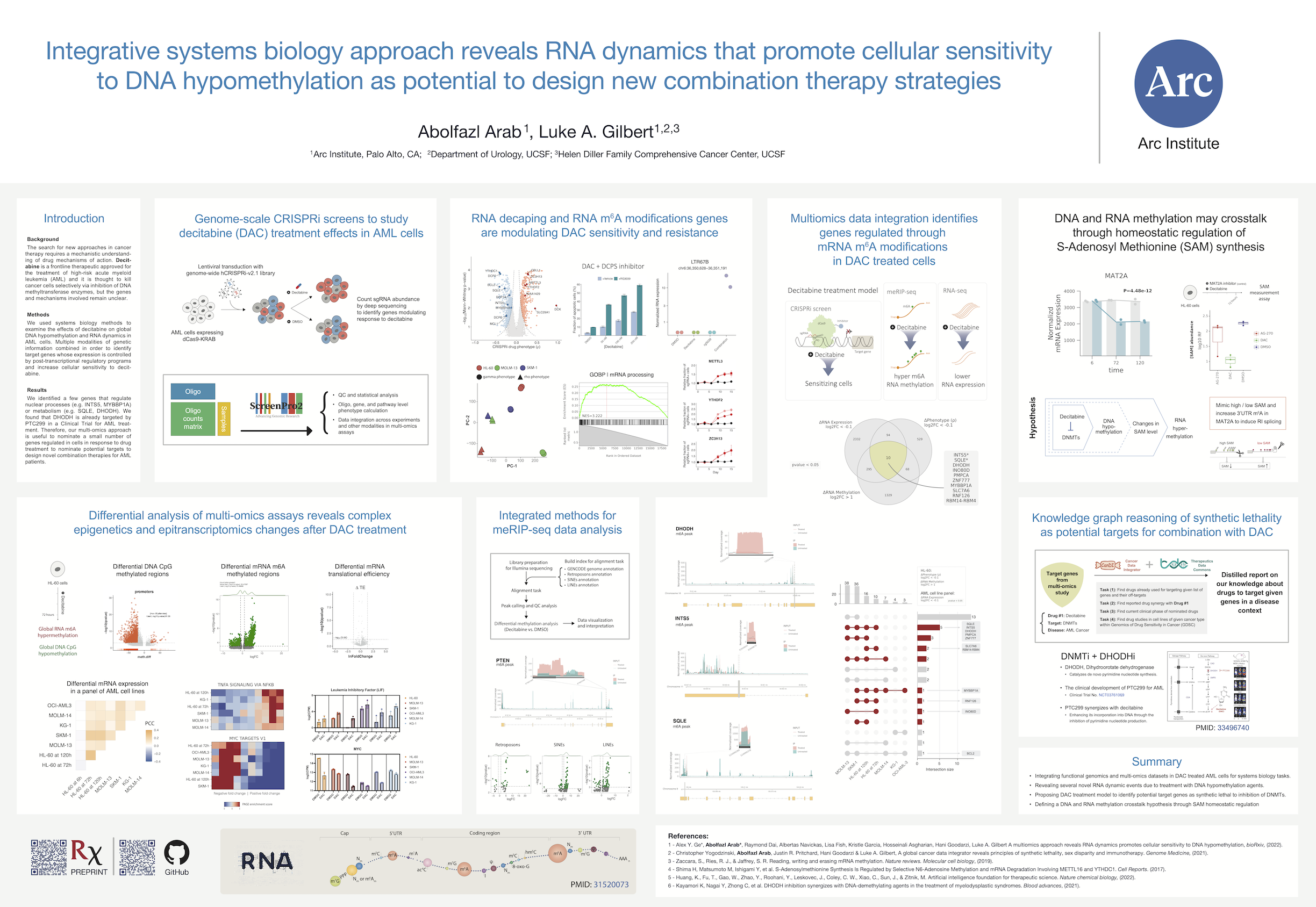

Background

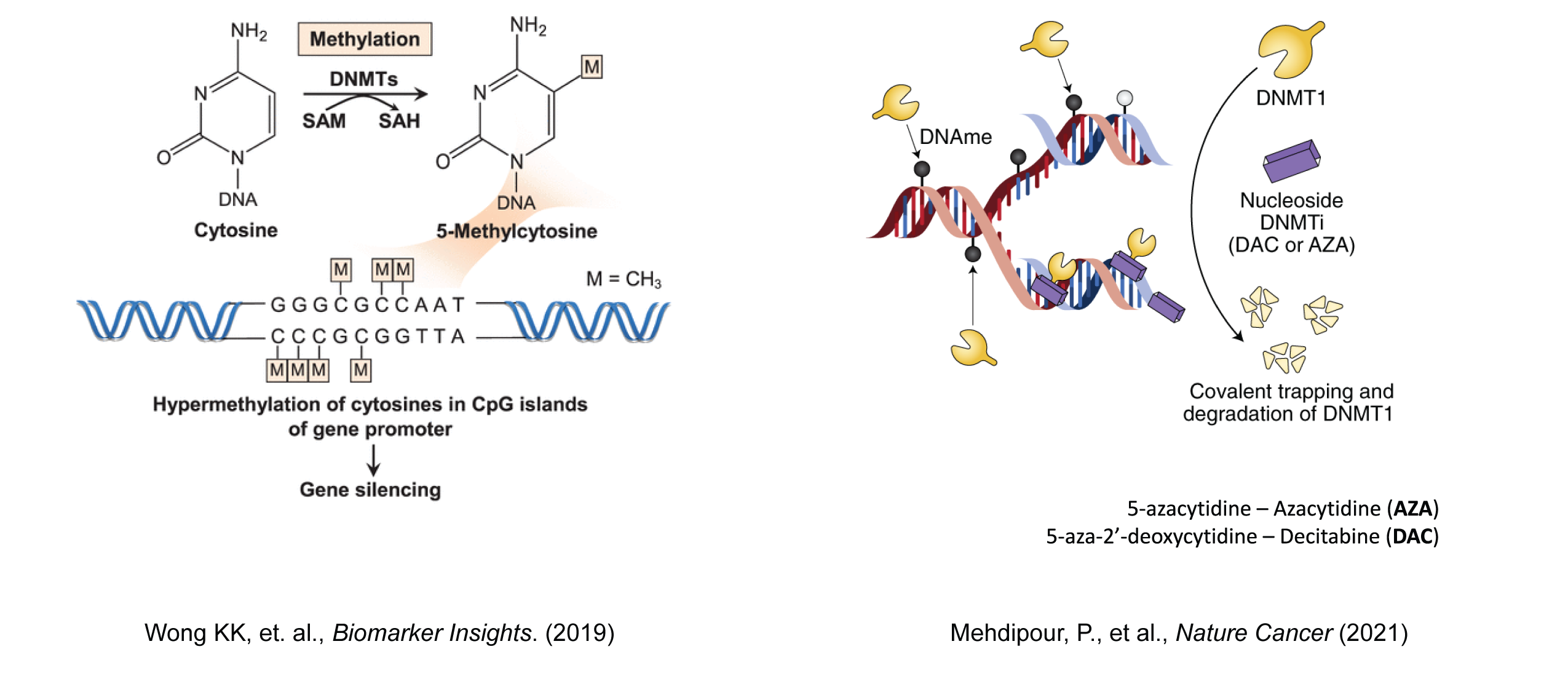

Decitabine, a DNA demethylating agent, is a drug with an epigenetic therapy mechanism of action and an FDA approved strategy to treat high-risk patients with AML cancer. I led part of a collaborative effort resulting in a publication titled “A multi-omics approach reveals RNA dynamics promotes cellular sensitivity to DNA hypomethylation”, where I contributed as a first author. I wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and integrated functional genomics (i.e., genome-wide CRISPRi screening in three AML cell lines) and multi-omics (i.e., RNA-seq for AML cell line panels, meRIP-seq, and Ribo-seq) datasets, mostly generated in Gilbert and Goodarzi labs at UCSF and Arc institute since 2018.

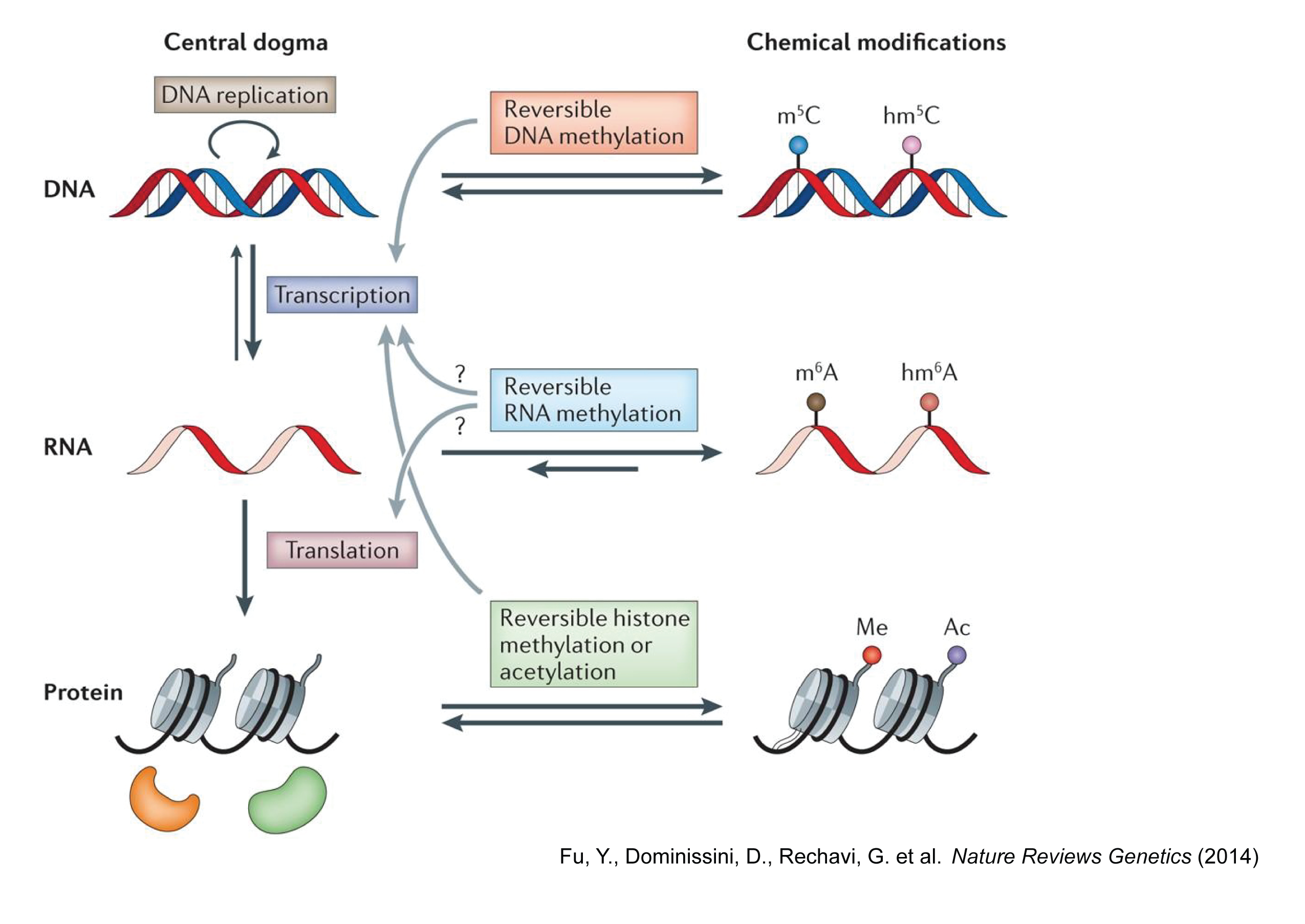

Central dogma of molecular biology

The central dogma of molecular biology is an explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system. Here, we are interested in the DNA and RNA methylation crosstalks and their impact on gene expression and cellular phenotypic responses to DNA hypomethylation.

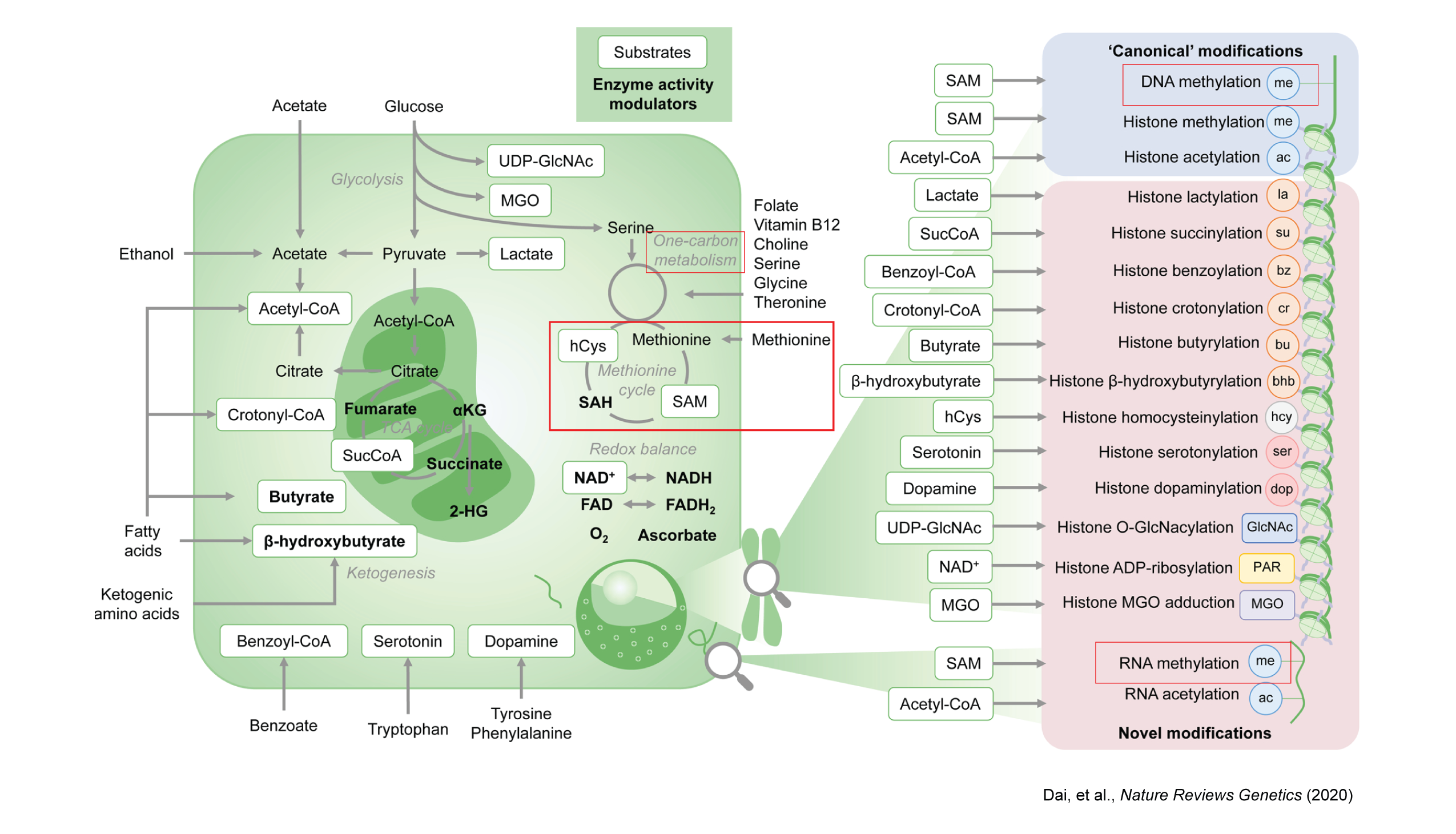

The evolving metabolic landscape of epigenetics

One-carbon metabolism is a series of interlinking metabolic pathways providing methyl groups for biological pathways, including DNA and RNA methylation. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) serves as the primary methyl donor for both DNA and RNA methylation modifications. SAM is synthesized by MAT2A and MAT2B proteins from methionine. SAM is then converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) by DNMTs, which are responsible for DNA methylation. Similarly, m⁶A RNA methylation, influencing RNA processing and translation, is facilitated by SAM’s methyl group transfer to adenosine.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a canonical epigenetic modification that plays a fundamental role in regulating gene expression and maintaining genomic stability. In this context, epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene function that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine bases of DNA, primarily occurring at CpG dinucleotides. CpG islands, regions with a high frequency of CpG sites, are often found in the promoter regions of genes and are particularly sensitive to methylation changes.

RNA methylation

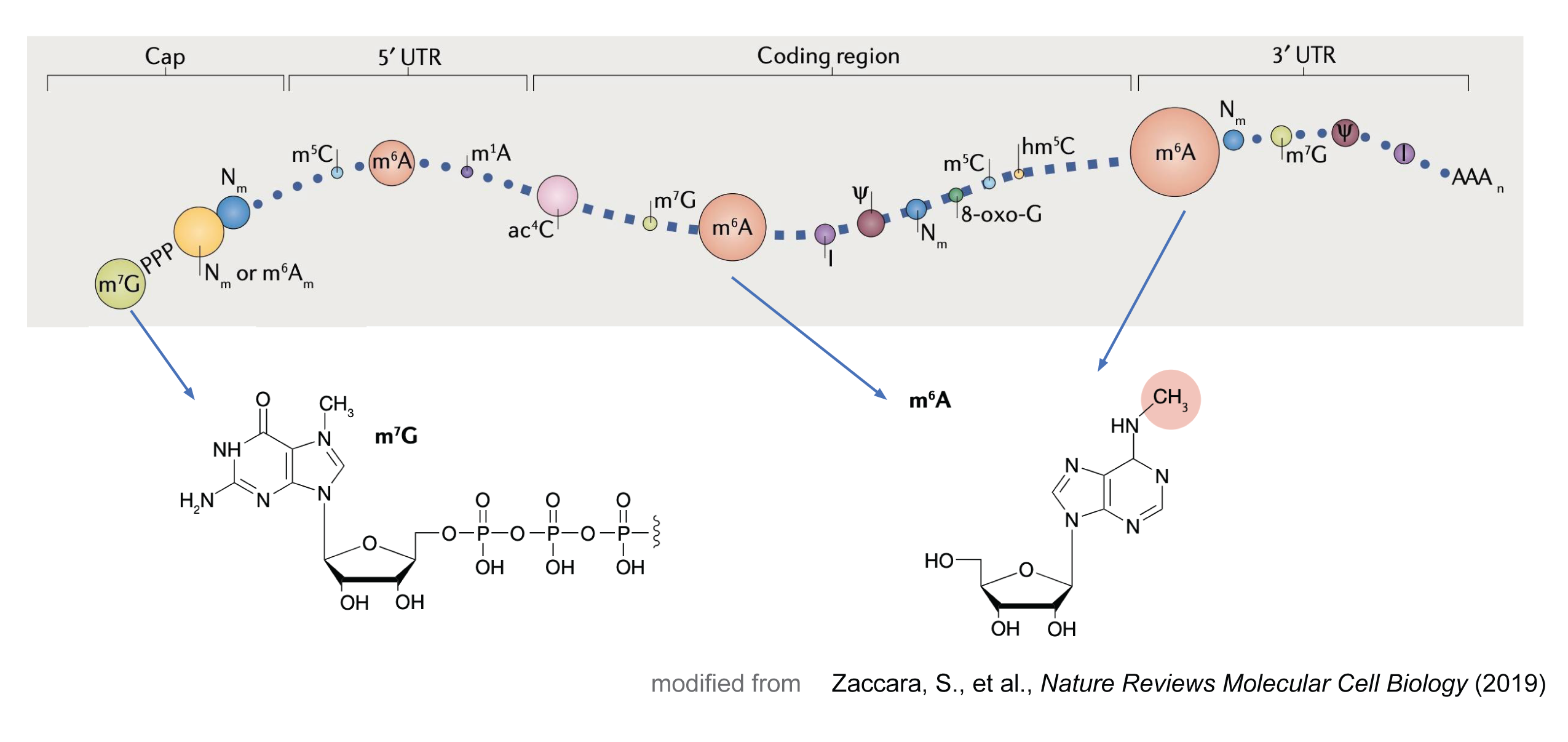

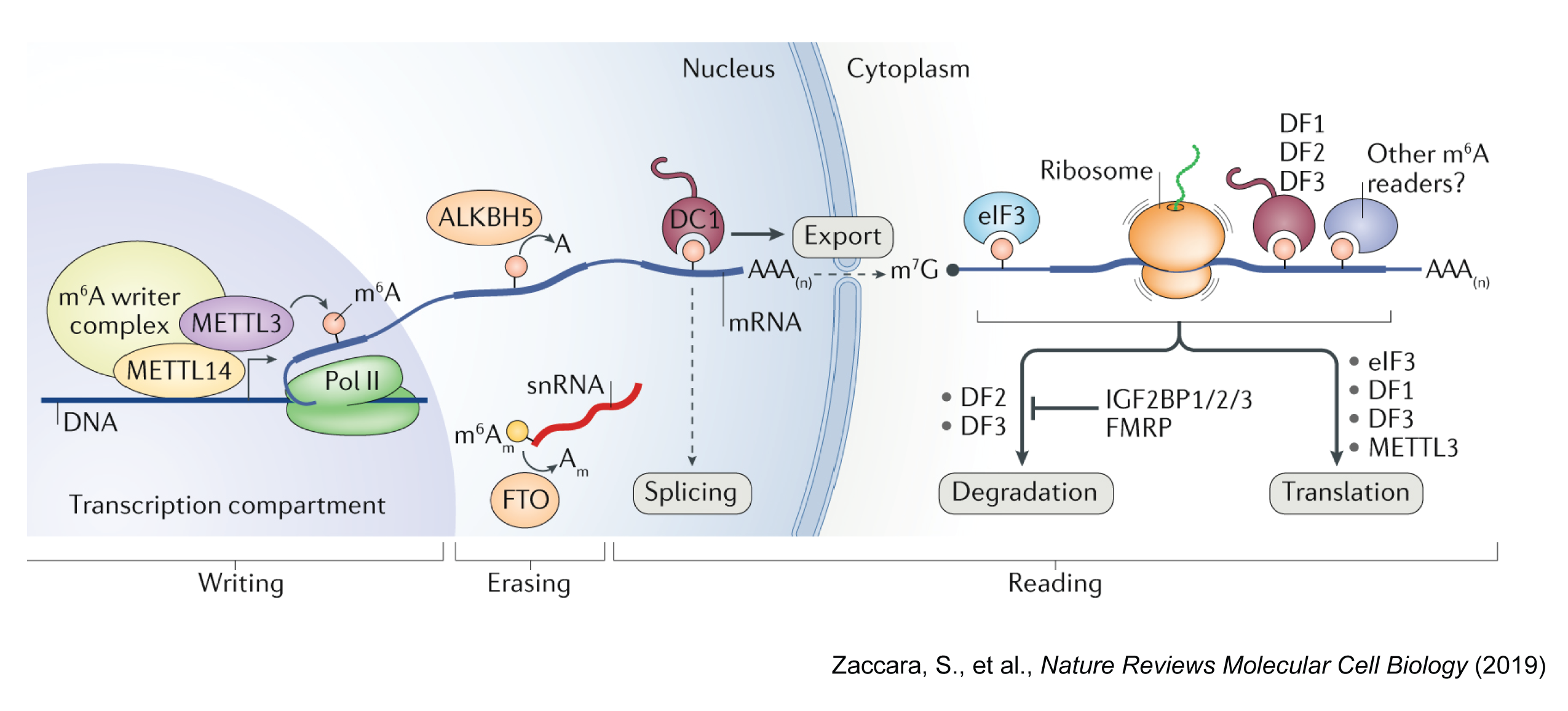

RNA methylation is a dynamic and reversible epigenetic modification that plays a critical role in regulating gene expression.

The most common RNA methylation is N6-methyladenosine (m⁶A), which is catalyzed by a methyltransferase complex (MTC) consisting of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP. The m⁶A is a prevalent modification in eukaryotic mRNA and is enriched in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) and near the stop codon. This modification is recognized by m⁶A reader proteins, such as YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2, and IGF2BP1-3, which regulate mRNA stability, localization, translation, and splicing.

RNA methylation changes is involved in various biological processes, including embryonic development, cell differentiation, and cancer progression. If you are interested to learn more about RNA methylation, I recommend reading these review papers:

- Zaccara, S., et al. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2019)

- Fu, Y., et al. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m⁶A RNA methylation. Nature Reviews Genetics (2014)

Functional genomics screens

Gilbert Lab is a pioneer in developing novel functional genomics tools and applying large-scale CRISPR interference and activation (CRISPRi/a) screens in drug discovery and genetic interaction studies.

ScreenProcessing is a pipeline developed by Dr. Max Horlbeck;

but I had to modify and extend it to fit our needs. My further experience with analysis of CRISPR screens in several

projects as research associate in UCSF and Arc Institute led me to develop a new tool for these types of analysis.

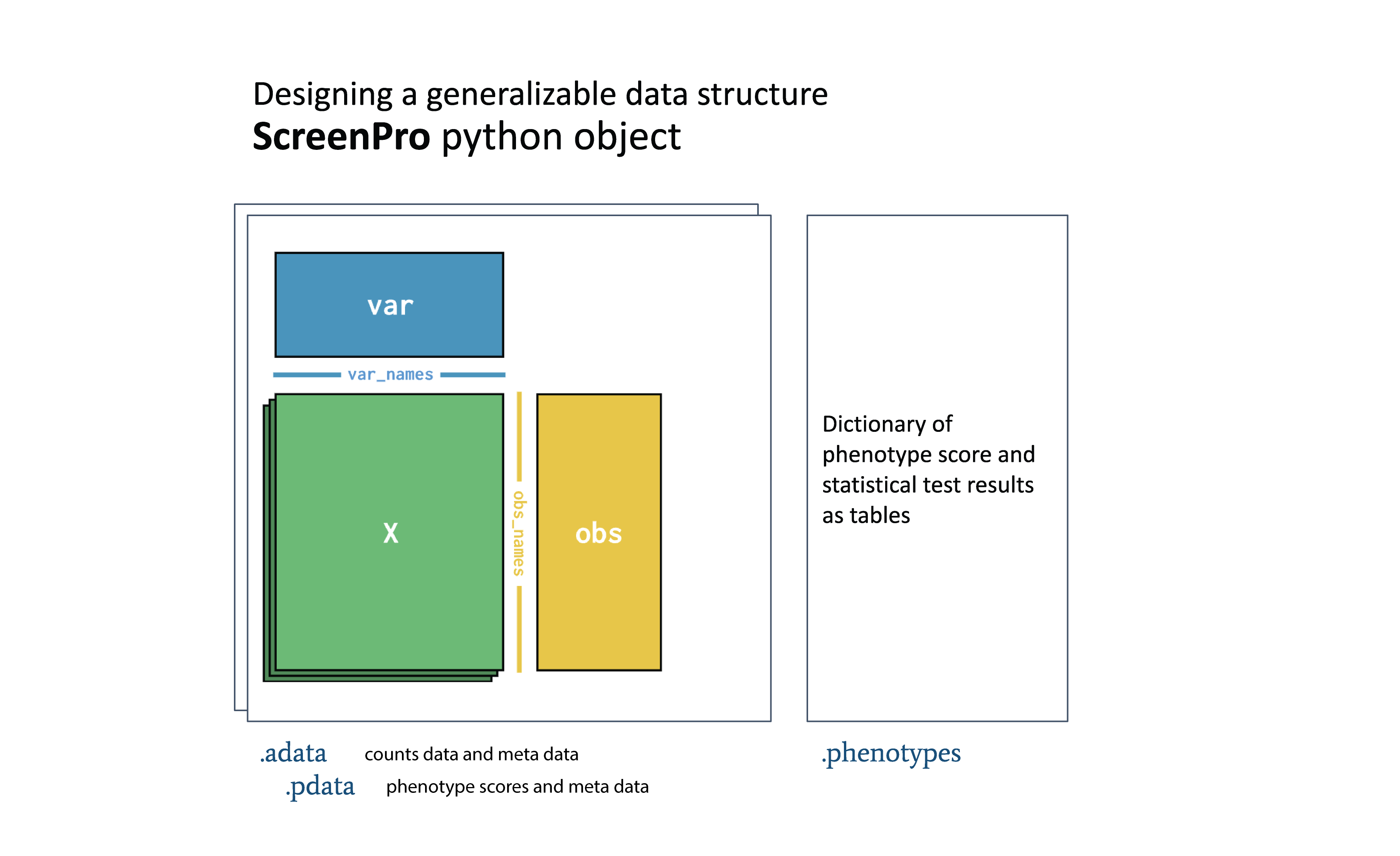

ScreenPro2 is a python tool I developed and in this project it helped me for data

exploration and integration. Notably, I mainly used AnnData to handle CRISPR screen datasets that enable scalable

downstream analysis and compatibility with other tools in scverse ecosystem.

ScreenPro2 is now covered in Arc Institute’s tools hub and currently, I’m working with the Multi-Omics Technology Center at Arc to improve it – https://arcinstitute.org/tools/screenpro2.

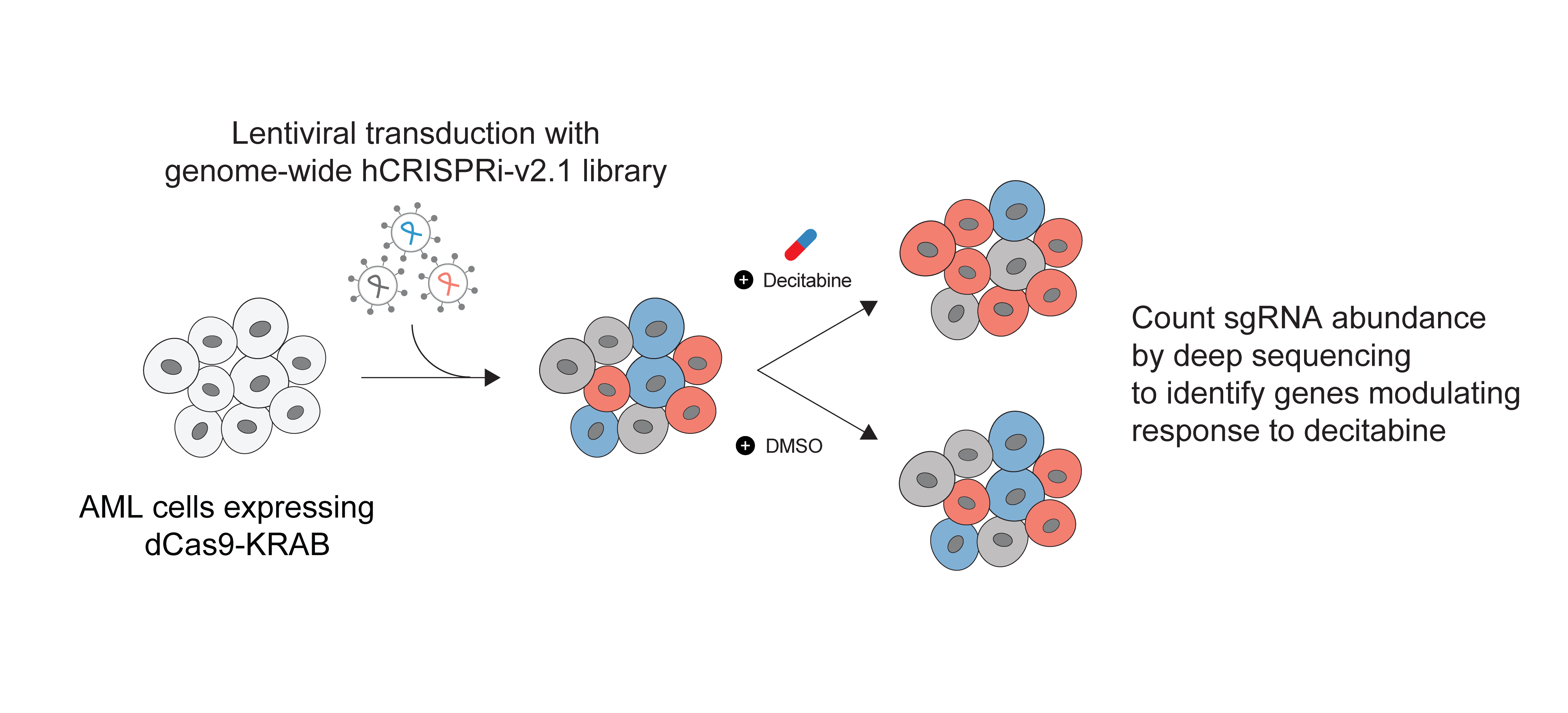

In this work we performed genome-scale CRISPRi screens to study decitabine treatment effects in AML cells.

To learn more about applications of functional genomics screens, I recommend reading these review papers:

- Przybyla, L., Gilbert, L.A. A new era in functional genomics screens. Nature Reviews Genetics (2022)

- Bock, C., et al. High-content CRISPR screening. Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2022)

Research questions and findings

As result of our work, we show that decitabine, as a DNA hypomethylating agent, causes global hyper m⁶A RNA methylation, not only on transcripts of protein-coding genes but also on the transcripts of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs). This observation is a novel phenotypic insight post decitabine treatment, raising questions about mechanisms behind DNA and RNA methylation crosstalks.

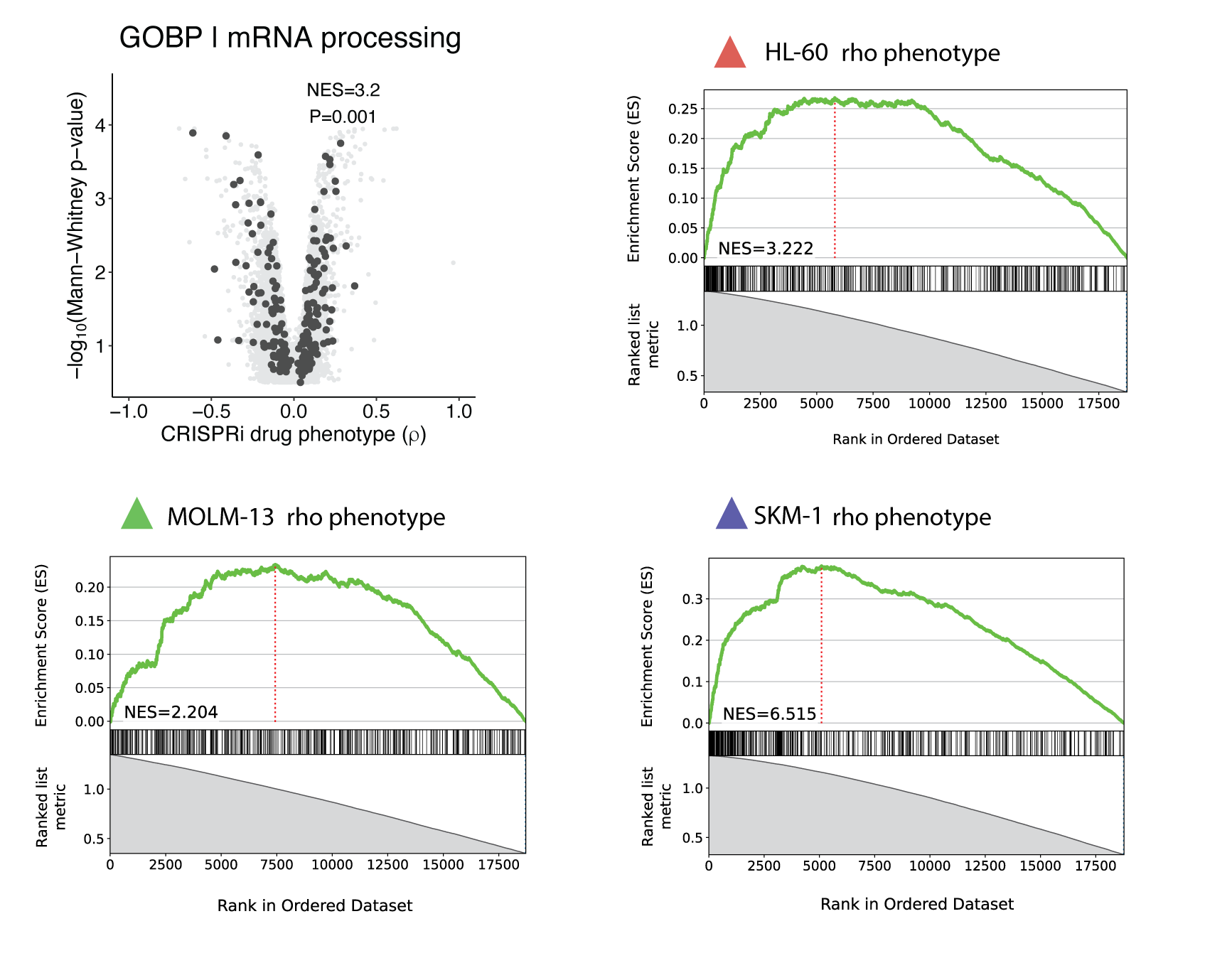

Genome-scale CRISPRi screens to study decitabine treatment effects in AML cells

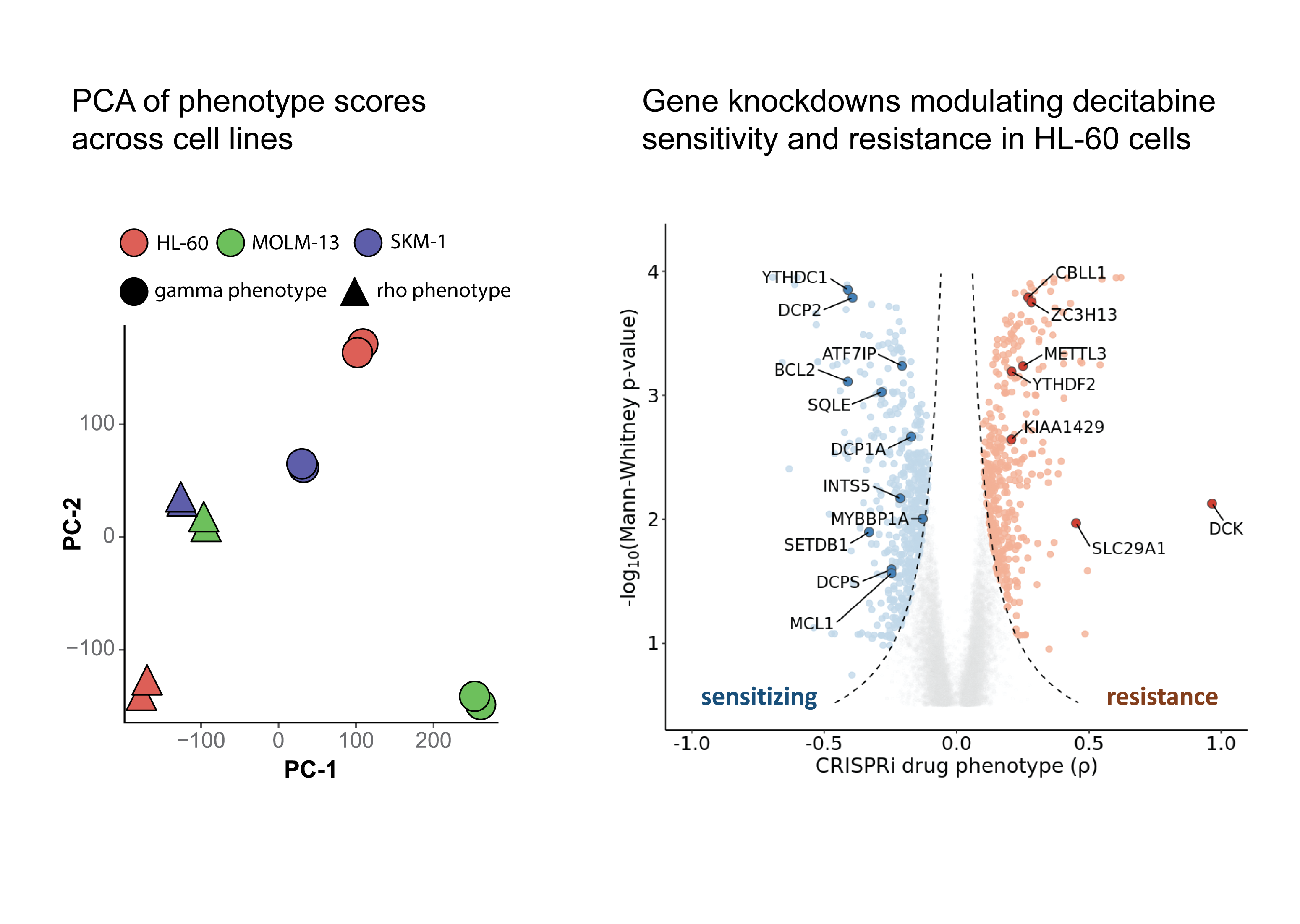

We performed genome-scale CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) functional genomics screen to identify genes that regulate cancer cell response to decitabine. We used HL-60, SKM-1, and MOLM-13 cell lines, which are representative of the different AML mutational backgrounds. Notably, the two cell lines classified as TP53-inactive (HL-60 and SKM-1), and the other cell line is TP53-wild-type cell line (MOLM-13).

We captured positive control genes whose knockdown is known to impact drug resistance, namely DCK, SLC29A1 and DCTD. Interestingly, we observed a lot of genes related to mRNA processing are enriched across top hits in our screens either as sensitizing or resistance genes. Additionally, we observed that repression of METTL3, an RNA m⁶A methylation writer gene, promoted resistance to decitabine across all three cell lines.

As expected from the heterogeneity of AML, in addition to common genes across cell lines, we also observed differences across cell lines with respect to genes that modulate differently in response to decitabine treatment.

For geneset enrichment analysis of CRISPRi screens, I used blitzGSEA but I defined some tricks to make it more informative regarding the message we want to convey in the manuscript. I got the gene ontology (GO) gene sets from MSigDB (here is where I keep the gene sets for these kinds of analysis as I’m regularly doing it – @abearab/pager – annotations). Then I defined two separate analyses:

- To identify smaller, focused pathways associated with drug sensitivity or resistance, I perform GSEA analysis on

genes ranked by ρ (rho) phenotype and defined minimum and maximum thresholds for gene set size when running the ‘gsea‘

function (

min_size=15andmax_size=150). Thus, positive normalized enrichment scores (NES) corresponded to gene sets enriched among positive ρ phenotypes (i.e., resistance phenotypes) and negative NES corresponded to gene sets enriched among negative ρ phenotypes (i.e., sensitivity phenotypes). - To identify broader pathways associated with drug response irrespective of ρ phenotype direction, I performed GSEA

analysis on genes ranked by

1 – pvalue(calculated for each ρ phenotype in ScreenProcessing or ScreenPro2) and set a high minimum threshold for gene set size (i.e.,min_size=200). Then we only report positive normalized enrichment scores (NES) that represent gene sets enriched by more significant p-value.

Using the second analytic approach, we observed that mRNA processing as general GO term enriched across top hits in all screens.

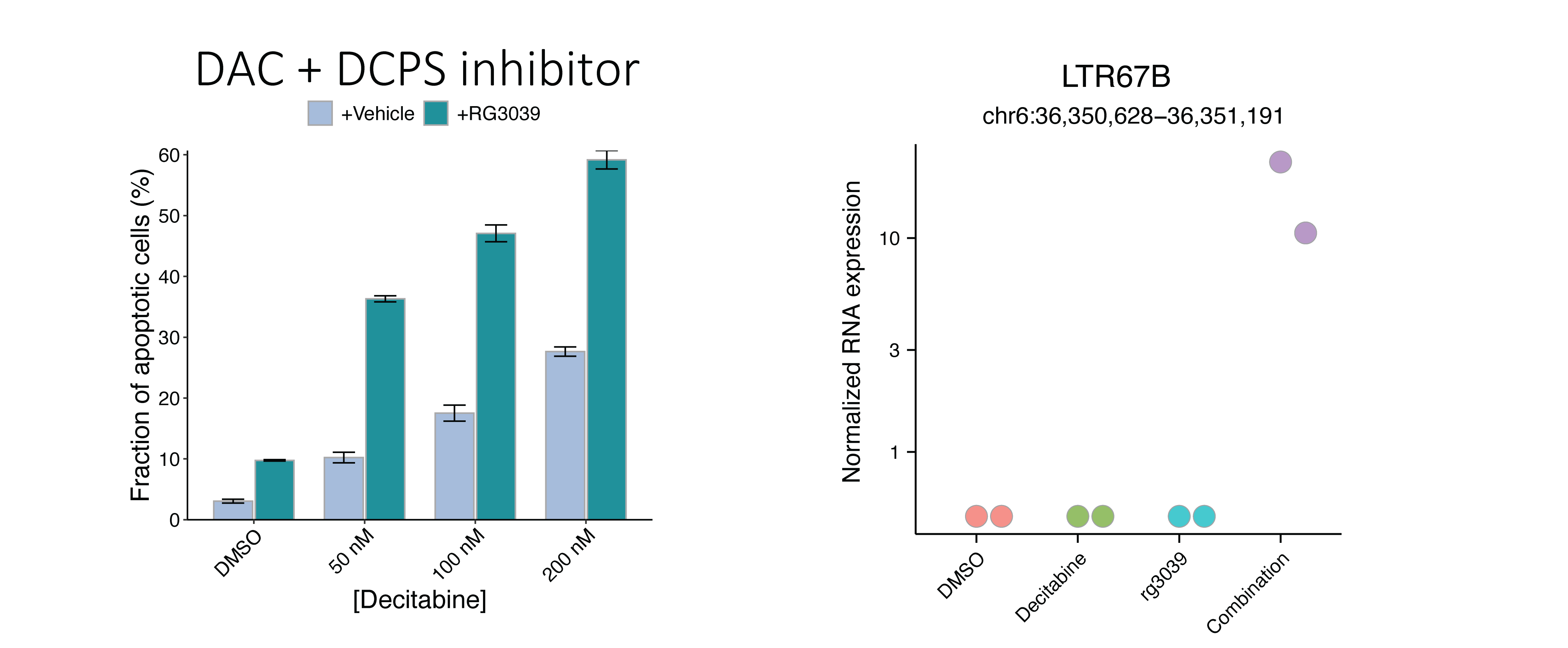

RNA decapping enzymes are modulating decitabine sensitivity and resistance

Initially, we observed that repression of DCPS, an RNA decapping enzyme, sensitized HL-60 cells. We then performed experimental validation to confirm the synergistic effect of DCPS inhibitor to combine with decitabine treatment. I used our RNA-seq data to investigate the effect of DCPS knockdown on gene expression in mono and combination treatment of decitabine. In addition to the protein-coding genes, I also investigated the effect of DCPS knockdown on ERVs expression. It is known that ERVs are epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation and decitabine treatment leads to their upregulation. I found that DCPS knockdown in combination with decitabine treatment leads to upregulation of ERVs. This is a novel observation that suggests a potential post-transcriptional regulation on ERVs expression by RNA decapping enzymes.

Repression of genes encoding RNA decapping enzymes such as DCP2 and DCPS sensitized HL-60 and SKM-1 cells, but not MOLM-13 cells, to decitabine treatment.

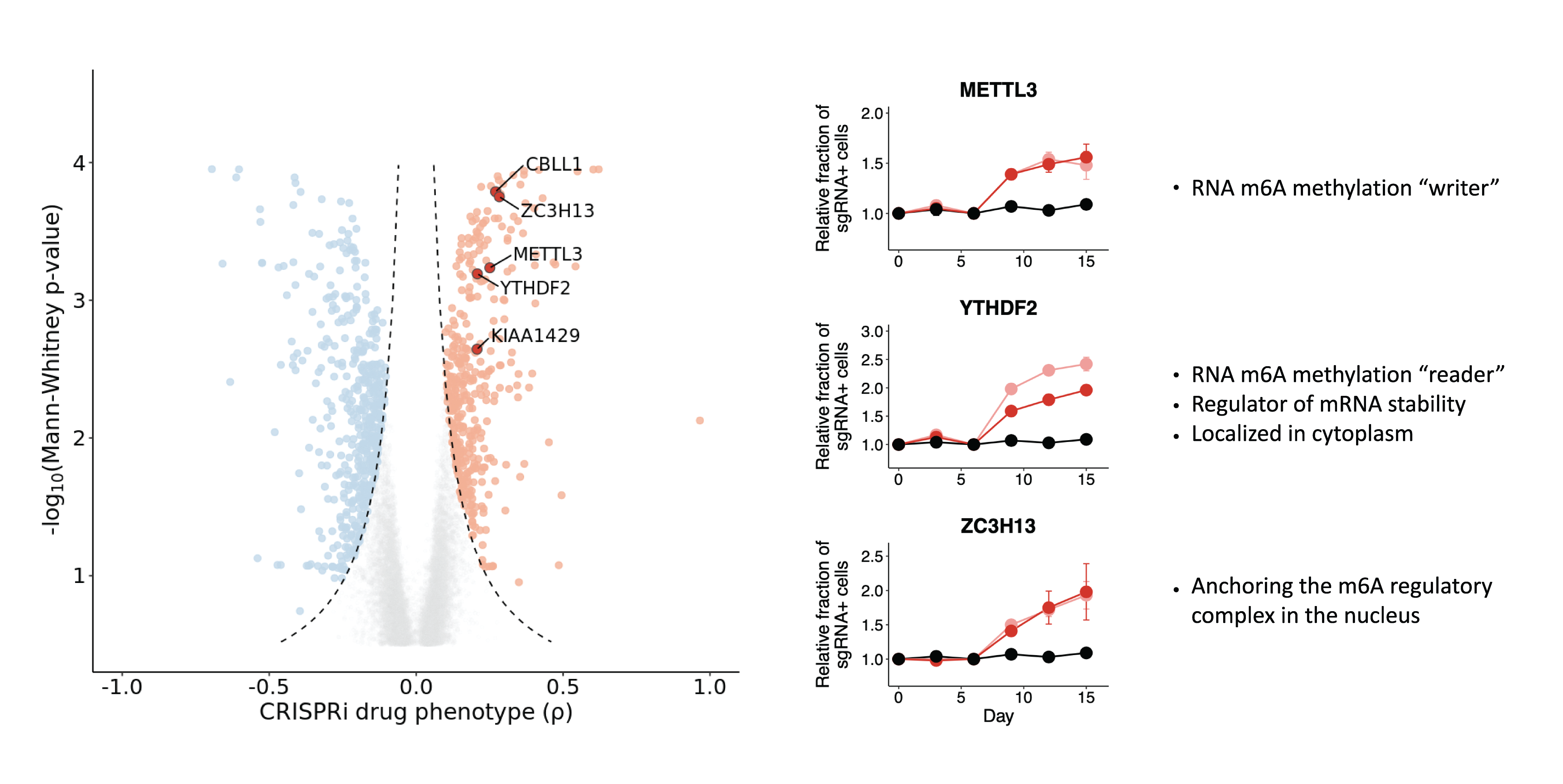

Depletion of m⁶A methyltransferase complex genes modulates decitabine resistance and sensitivity

As mentioned above, we observed that repression of RNA m⁶A methyltransferase complex gene, promoted resistance to decitabine. We then performed experimental validation to confirm the resistance phenotype in HL-60 cells.

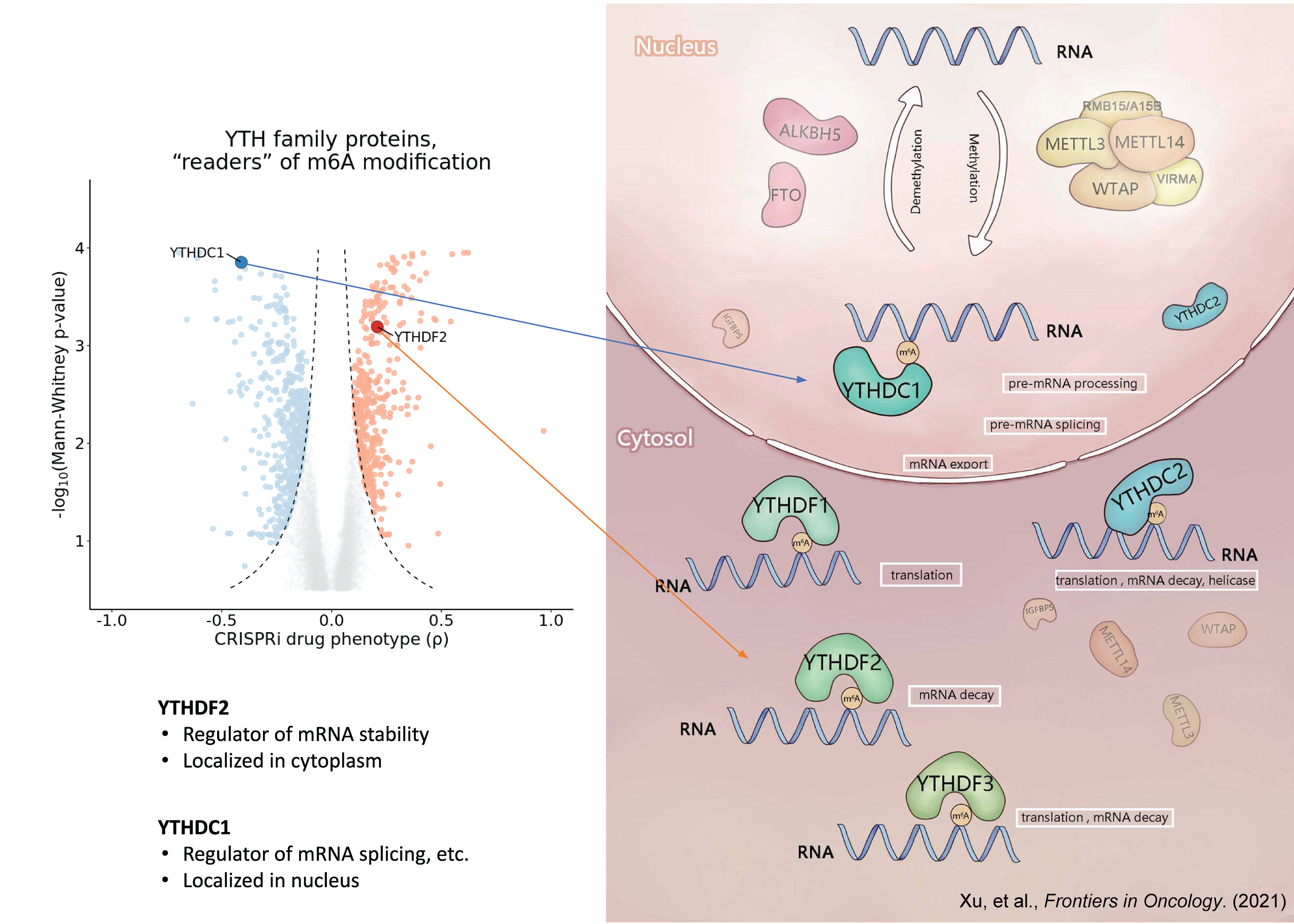

The fate of m⁶A-modified mRNA is determined by the m⁶A “reader” proteins. There are five human m6A “reader” proteins classified into two classes according to their binding pocket features:

- YTHDC1 and YTHDC2

- YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3

We observed that repression of YTHDC1 sensitized HL-60 cells to decitabine treatment and repression of YTHDF2 promoted resistance to decitabine treatment.

In my literature review, I found these two papers very useful and informative regarding the role of YTH proteins:

- Zhou, J., Wan, J., Gao, X. et al. Dynamic m⁶A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature (2015)

- Xu, Z., et al. RNA methylation preserves ES cell identity by chromatin silencing of retrotransposons. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2021).

Taken together, these results suggest that m⁶A-modification of mRNA may play a role in regulating the response to decitabine treatment and we wanted to investigate this further using a multi-omics approach.

Differential analysis of multi-omics assays reveals complex epigenetics and epitranscriptomics changes

In September 2019, I joined Goodarzi Lab at the University of California, San Francisco and my role as research associate was joint with Gilbert Lab. By that time, this project was already in progress and some initial observations were confirmed by data analysis and experimental validation. However, extensive multi-omics data integration was not performed yet and that was my starting point!

Since undergraduate, I studied several papers from Dr. Saeed Tavazoie’s lab (tavazoielab) at Princeton and then Columbia which shaped my perspective on systems biology. Dr. Hani Goodarzi was a PhD and then postdoc in Tavazoie lab and working with him was a great opportunity for me to learn more about the tools he developed in Tavazoie lab and gain practical experience with them. Over time, I learned more and more about the computational basis of systems biology tools and I wrote extensions to these to enable biological interpretations in this project.

I started by reanalyzing all the omics data generated by both labs using harmonized genomic annotation and developing pipelines and scripts for reproducible and scalable data analysis. My scripts and pipelines are available in GitHub.

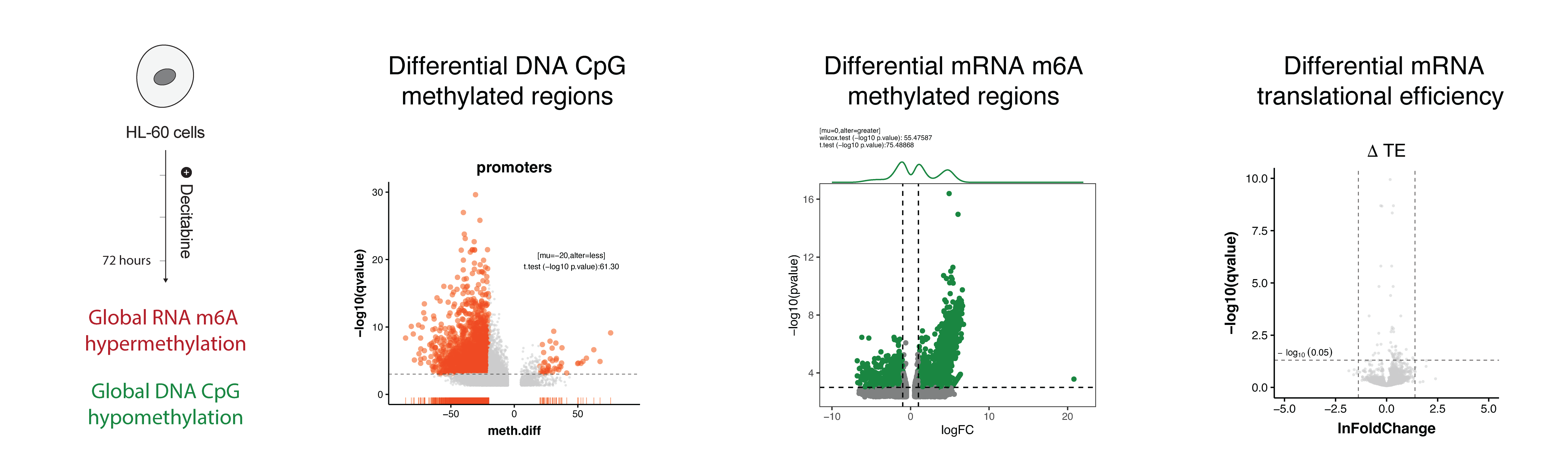

In summary, we aimed to integrate comparisons between treatment with decitabine or DMSO. In a time-series experiment, HL-60 cells was treated with decitabine or DMSO and collected samples at 6, 72, and 120 hours post-treatment. The meRIP-seq, Ribo-seq, and all CRISPRi screens were performed at 72 hours post-treatment. In addition to our datasets, I found a DNA methylation dataset for HL-60 cells treated with decitabine or DMSO. Finally, we had RNA-seq datasets for a panel of AML cell lines.

I developed pipelines to perform differential analysis for each omics dataset and integrate the results. Here is a list of reproducible pipelines and other repositories developed as part of this project (I have already used them in other published or unpublished projects):

- Differential gene expression analysis: Salmon-tximport-DESeq2 pipeline

- Differential RNA stability analysis: STAR-featureCounts-REMBRANDTS-limma pipeline

- Integrated methods for meRIP-seq data analysis – https://github.com/abearab/imRIP

- Pathway analysis using PAGE algorithm and downstream analysis – https://github.com/abearab/pager

- Scripts for mapping NGS reads to HERVs – https://github.com/abearab/HERVs

In general, I believe that gathering high quality context-specific big data and carefully integrating them provides powerful resources for data-driven hypothesis generation toward finding previously unknown biological phenomena.

Okay, let’s get back to the results!

In the DNA methylation dataset, we observed that decitabine treatment leads to global hypomethylation of DNA (left) – as expected. But surprisingly, our meRIP-seq data showed that decitabine treatment leads to global hypermethylation of RNA (middle). Initially, we thought this may cause changes in RNA translation efficiency, however, our Ribo-seq data showed that there is almost no changes in translational efficiency changes (right).

We also performed differential expression and stability analysis of RNA-seq data and observed that decitabine treatment leads to upregulation of some genes and downregulation of others. Although, we discussed the RNA stability changes (i.e. prediction of RNA stability from RNA-seq using REMBRANDTS)) in the manuscript, I did not include them in this blog post.

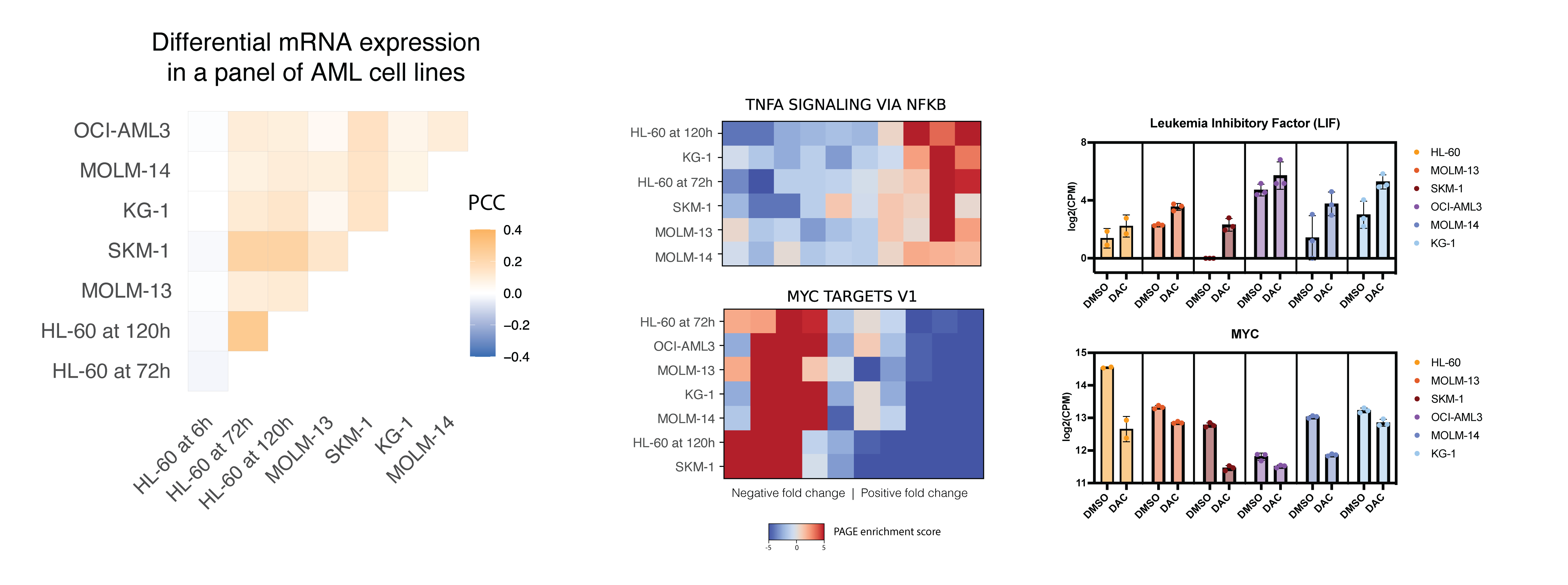

To highlight the complexity of the data, I plotted the upregulated and downregulated some genes and pathways here.

For this, I used a python implementation of the PAGE algorithm (pypage)

together with my scripts for manipulating the results (pager). I think my add-on

scripts are useful for biological interpretation (I should note that some scripts in pager came from my slack

conversations (!) with Dr. Goodarzi and I just included them in this repository for reproducibility).

Here I’m showing one pathway being upregulated across all AML cell lines and another pathway being downregulated across all AML cell lines. For each, I’m showing one of the genes in the pathway and the corresponding gene expression changes. Since the heatmap is showing one pathway across all cell lines, let’s call it onePAGE! To interpret the heatmap, you need to understand that expression fold changes for each cell line (rows) are ranked from low to high and then splitted into 10 bins. The color of each bin in the heatmap shows the PAGE enrichment score for that bin, i.e. the enrichment of given geneset in that bin.

- HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB is upregulated across all cell lines.

- HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 is downregulated across all cell lines.

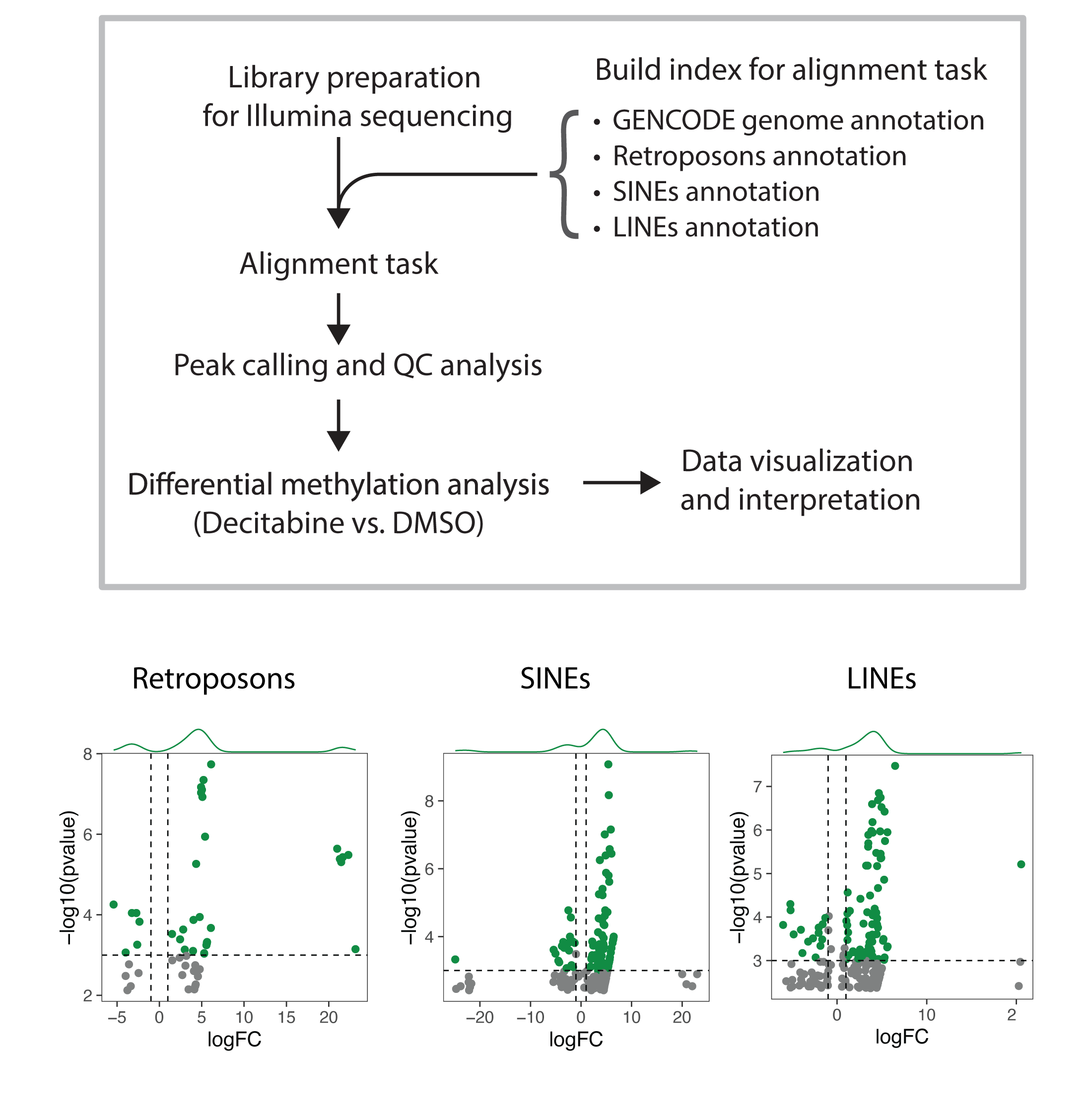

As I learned more about this topic, I hypothesized that decitabine induced RNA hypermethylation may also occur on transcript of ERVs in addition to mRNAs. I extended my pipeline to map NGS reads to HERVs, and then I perform differential methylation analysis. Interestingly, I observed that decitabine treatment leads to hypermethylation of some ERVs and hypomethylation of others; although, the majority of ERVs are not detected most likely due to the lack of expression.

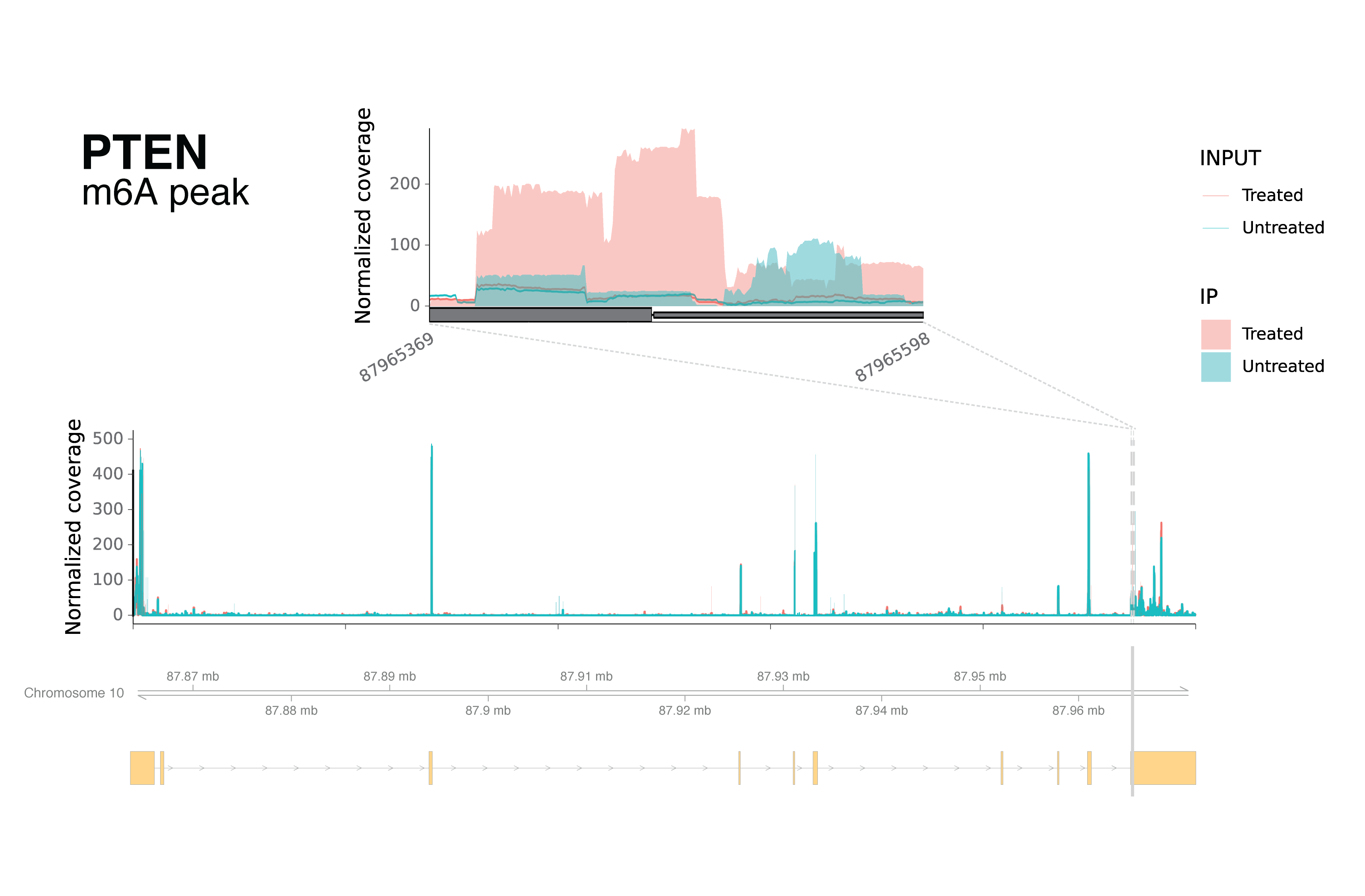

As another evidence for the complexity of RNA dynamics in response to decitabine treatment, I noticed that PTEN transcript has both hyper and hypo-methylation in different regions of the transcript.

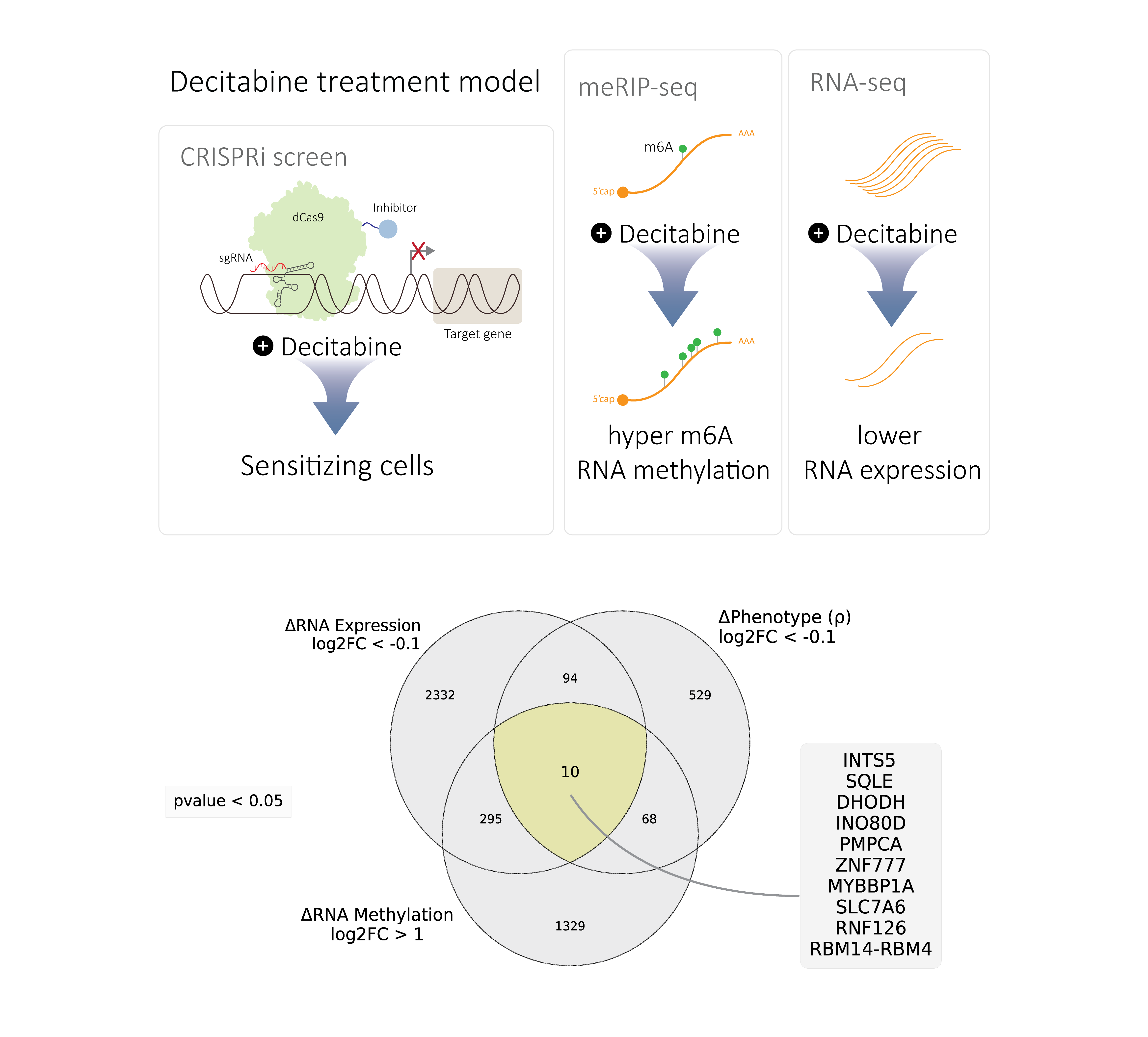

A treatment model to nominate genes whose RNA hypermethylation induces RNA decay and sensitize cells

In the follow-up investigations, we defined a conceptual model through a multi-omics data integration workflow, suggesting a small number of target genes in which their expression decay through RNA methylation may cause sensitivity to decitabine-treated AML cells.

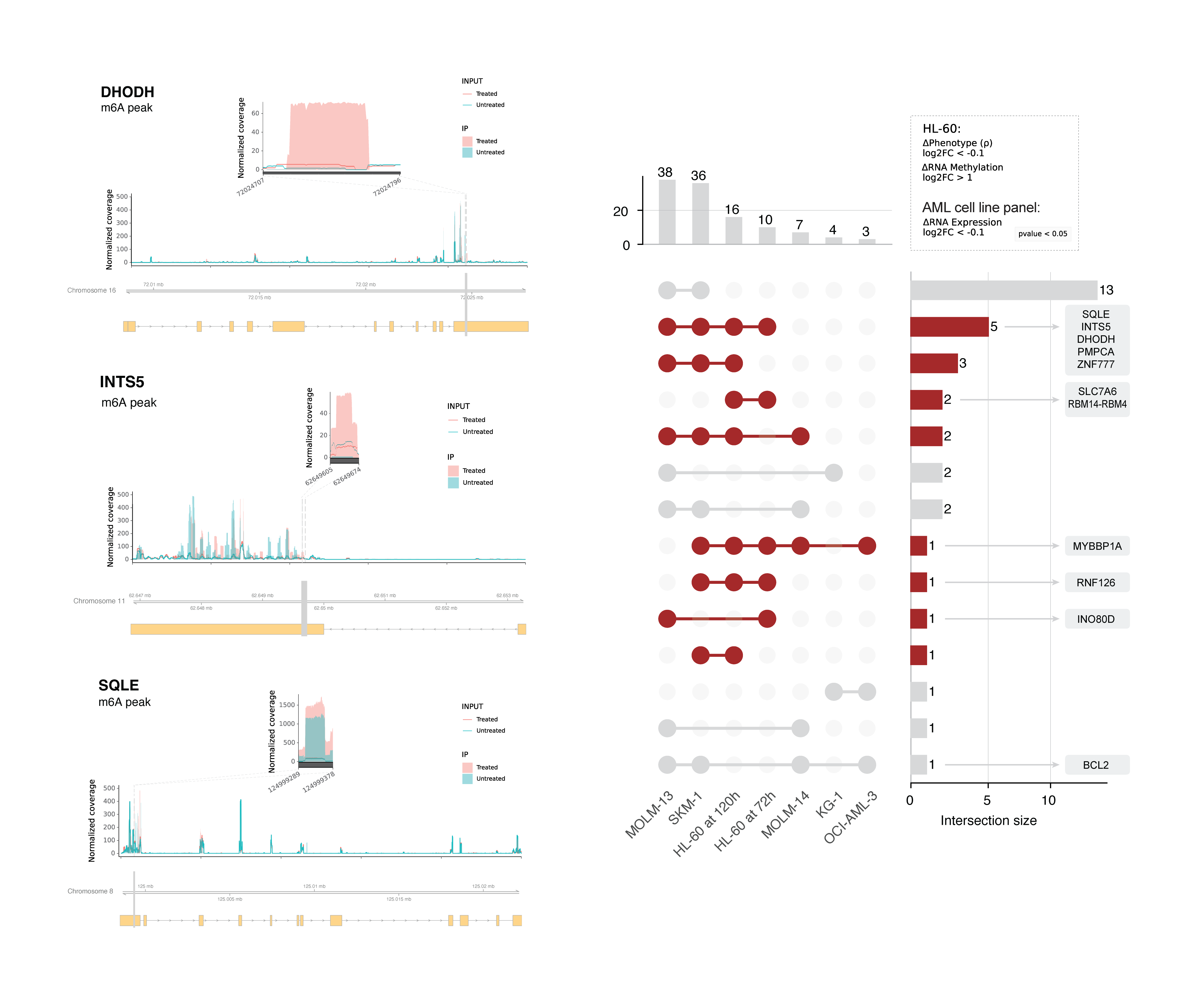

These genes collectively regulate nuclear processes (INTS5, INO80D, ZNF777, MYBBP1A, RNF126, RBM14-RBM4)) or metabolism (SQLE, DHODH, PMPCA, SLC7A6). From this list we selected SQLE and INTS5 and validated that their mRNA abundance is decreased and m⁶A methylation is increased in HL-60 cells following treatment with decitabine.

These results suggest we have identified a small number of mRNAs that are likely downregulated due to increased m⁶A methylation following decitabine treatment and that these same genes are functionally important for cellular response to decitabine. We extended this analysis to other AML cell lines and observed that the expression of some of these genes are also decreased in other AML cell lines following decitabine treatment. This suggests that these genes may have a consistent pattern of regulation and function across diverse AML contexts.

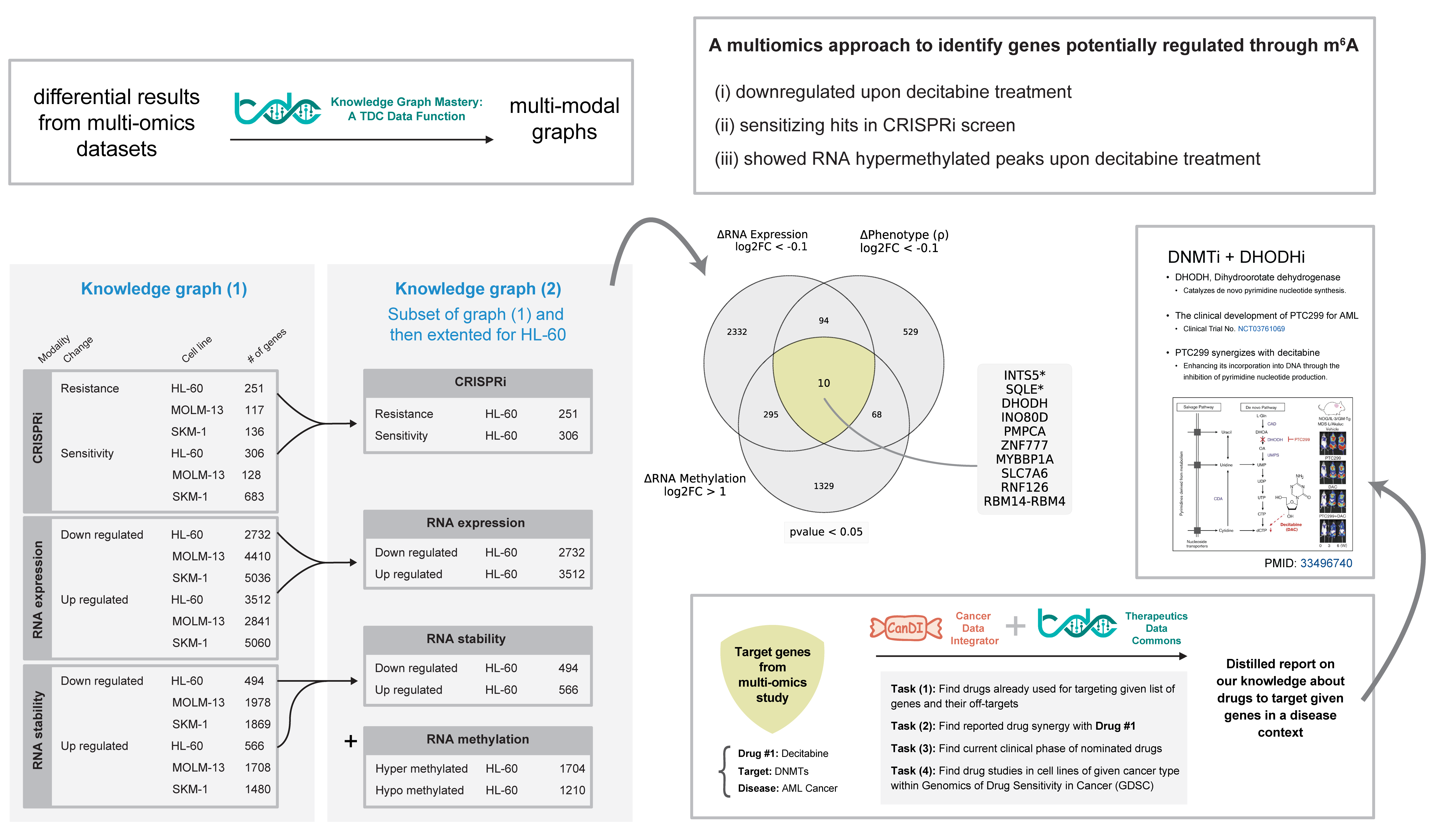

Knowledge graph reasoning of synthetic lethality as potential targets for combination with decitabine

Our results suggest that decitabine treatment leads to RNA hypermethylation and RNA decay of some genes. I aimed to look for any available drugs that already target these genes and can be used in combination with decitabine in the treatment of AML. To identify potential targets and treatment strategies for combination with decitabine, we used a knowledge graph reasoning approach.

Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) is an open-source initiative to enable researchers to use artificial intelligence capability across therapeutic modalities and stages of discovery. As part of a project with Dr. Marinka Zitnik, I developed a knowledge graph data function that integrates data from multiple sources into a knowledge graph which is compatible with the Precision Medicine Knowledge Graph (PrimeKG). Theoretically, this harmonized format allows us to combine a context-specific knowledge graph and PrimeKG to perform knowledge graph reasoning or run simple queries on common information between the two knowledge graphs.

Therefore, I created a context-specific knowledge graph for decitabine treatment in AML using our multi-omics data. Although, this contextual knowledge graph can be used for several downstream analyses, I used it to identify potential combinations of decitabine with other drugs in the context of AML.

To enable more meaningful queries on cancer datasets, I incorporated another resource that we developed previously in Gilbert Lab – Cancer Data Integrator (CanDI). CanDI is a data retrieval and indexing framework that allows integration of publicly available data from different sources (e.g. DepMap) and enables to take full advantage of efforts to map cancer cell biology. For example, CanDI allowed me to integrate data from DepMap and TDC to identifying experimental evidence in in AML cell lines for drugs that I found to be combined with decitabine.

By literature search, I confirmed that at least one of the DHODH inhibitors is already in clinical trials for AML and reported to be synergistic with decitabine in AML cells.

I think this analysis suggests that our model can be used to identify potential targets and treatment strategies for cancer therapy.

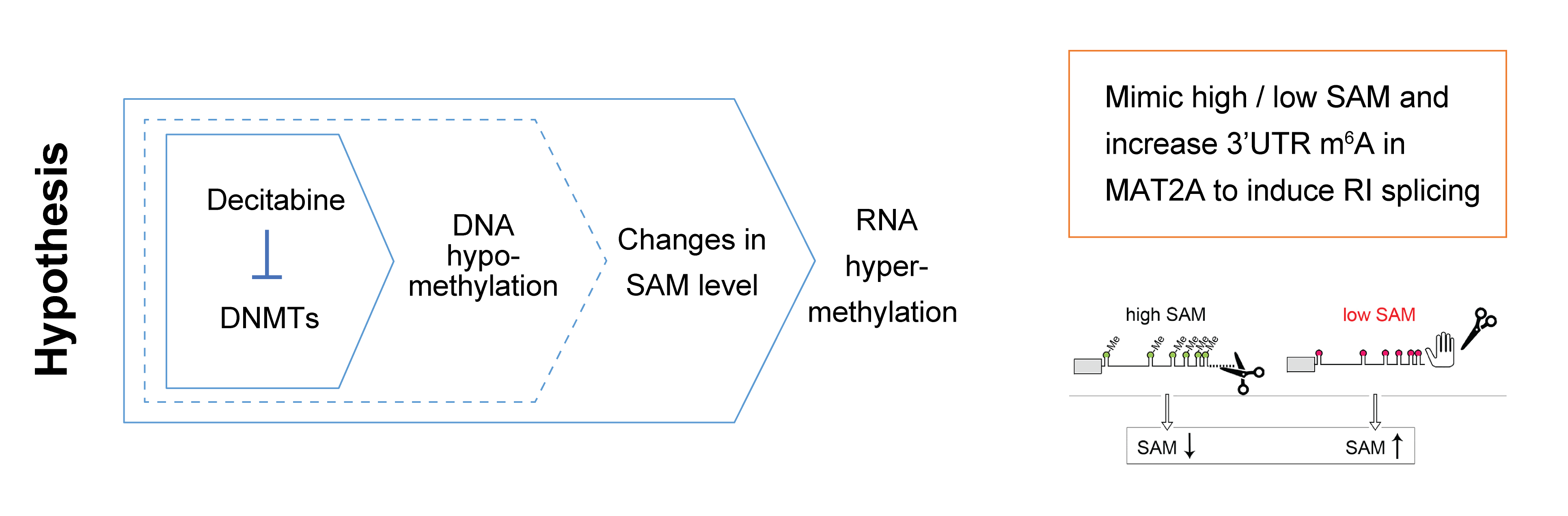

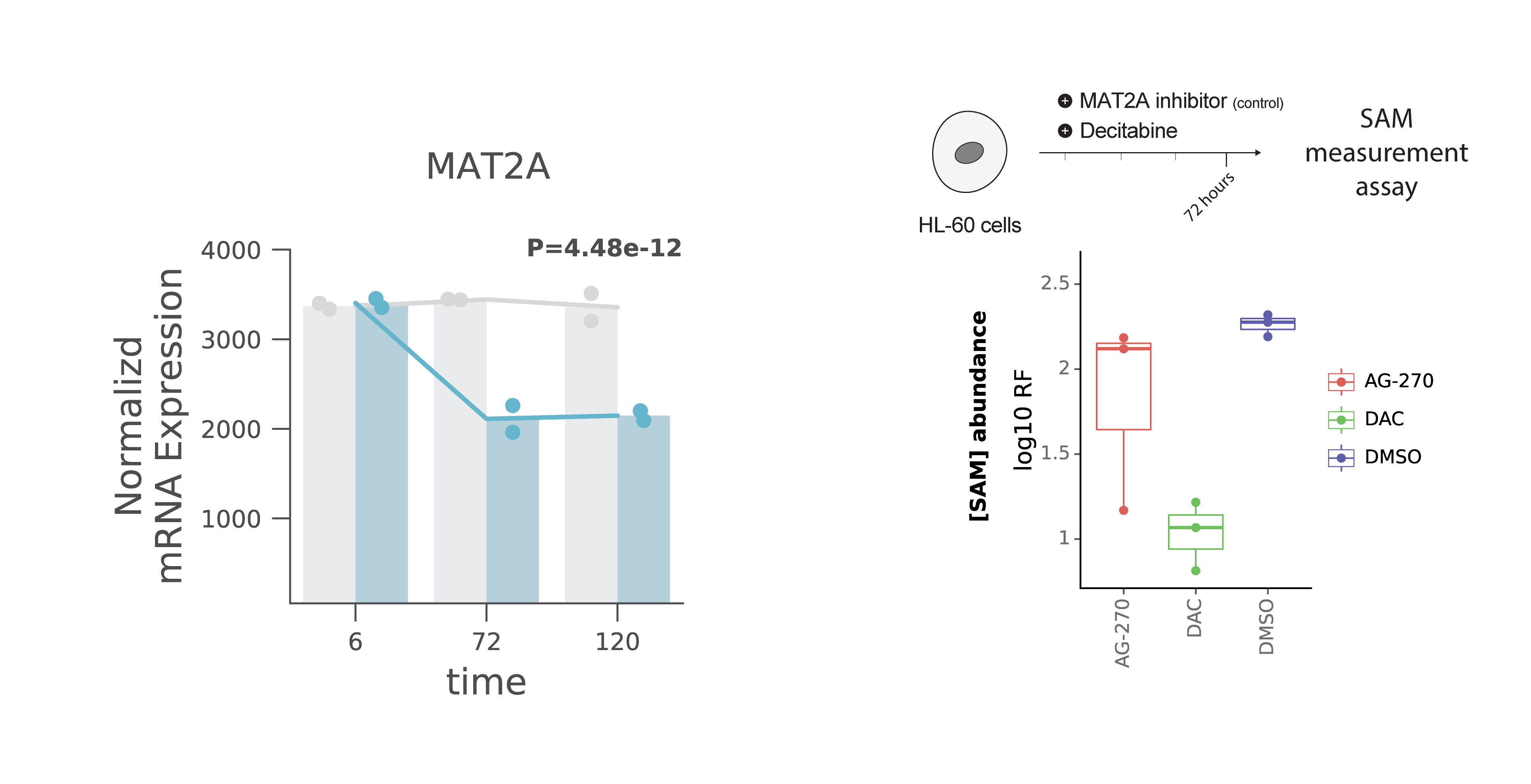

DNA and RNA methylation may crosstalk through homeostatic SAM synthesis

Although systems biology approaches are powerful to identify potential mechanisms, they are not sufficient to prove them. Biology experiments are required to validate the hypothesis and these experiments needs biochemistry, cellular biology, and molecular biology expertise. At Arc Institute, I was lucky to have access to these resources both in terms of training and facilities which enabled me to design and perform experiments to test some of our hypotheses.

Dr. Gilbert and I discussed a potential mechanism for DNA-RNA methylation crosstalk through changes in SAM abundance. Generally, we know that DNA methylation is a global phenotype while the majority of CpGs are methylated in human cells. Thus, decitabine’s inhibition of DNMT enzymes, DNA methylation writers, may lead to accumulation of SAM and then, that may cause the global hypermethylation of RNA – our key observation.

There are several studies about homeostatic regulation of SAM synthesis that involves dynamic m⁶A modifications in the MAT2A 3′ UTR and it’s role on splicing regulation – Shima et al., Cell Reports (2017) and Pendleton, Kathryn E et al. Cell (2017). As a mechanism, I think maybe the decitabine treatment’s DNA hypomethylation effect on SAM levels in cells and this mimics the effect of SAM changes on MAT2A 3′ UTR methylation and splicing.

To answer this question, I worked with my colleague at Arc Institute, Dr. Jackie Carozza, who is a senior scientist in the Li lab; I met her for the first time on our first day on-boarding at Arc Institute and kept my connection with her! Relying on her biochemistry expertise and my access to facilities within the Arc community, I designed an experiment to test our hypothesis.

Basically, I had three conditions, first cells treated with DMSO as negative control, second cells treated with AG-270 which is a MAT2A inhibitor (enzyme for SAM synthesis) as a positive control, and finally cells treated with decitabine. To enable this experiment, I used a fluorescence assay kit to measure SAM concentrations. Initially, I got help from Dr. Carozza and we performed several pilot experiments to set up a protocol. Finally, I collected all my cells as the experiment was designed and then, I measured the SAM abundance in the three conditions discussed above. As expected, the SAM abundance decreased in the AG-270 treated condition (positive control). Interestingly, I saw the SAM abundance even went lower than the AG-270 treated cells. I collected cells in 72 hours post-treatment so we think maybe the SAM abundance is going up in the earlier time points post drug treatment.

However, this experiment opens more biological questions as expected in any hypothesis-based experiments! For example, it’s not clear if the SAM abundance has an spike in the earlier time points post drug treatment and that requires more experiments. Also, it’s not clear if the SAM abundance is the only mechanism for DNA-RNA methylation crosstalk.

Poster presentations and preprint

Preprint on bioRxiv: v1, v2, v3

https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.14.518457

Our first preprint was posted on bioRxiv on December 14, 2022 and the third version was posted on December 07, 2023. Although, this work is not yet published, but I think this is a good example of how I can work on a project from the beginning to the end. I was involved in all aspects of this project including experimental design, data generation, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. I also presented in multiple lab meetings and institutional seminars to receive feedback from other researchers and colleagues.

The 1st NYC RNA Symposium 2023

https://www.nycrnasymposium.com/

I presented a poster from my works in this project at the 1st NYC RNA Symposium 2023. I received positive feedback from conference organizer, Dr. Sara Zaccara, and participants. Engaging with keynote speaker Dr. Anna Pyle led to valuable discussions on drug treatment-induced mis-splicing, illustrating the broader research possibilities as future works.

The Bay Area RNA Club 2023

I presented at the Bay Area RNA Club 2023. I enjoyed the opportunity to present my work to a broader audience and RNA biologists. I received valuable feedback from the audience specifically on the RNA modifications and their role in phenotypes upon decitabine drug treatment.

Future directions and career goals

Here, I’ve done my best to summarize my research journey by focusing on this project. However, this is just one of the many projects that I’ve been involved in during my research experience prior to graduate school. I learned a lot scientific lessons and skills from my mentors and colleagues. I think I’m ready to start my PhD journey!

I believe that CRISPR systems are powerful tools for functional genomics research, but they are not limited to that. In 2023, some news came out that the world’s first CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing therapy approved:

- UK first to approve CRISPR treatment for diseases: what you need to know.

- The world’s first CRISPR therapy is approved: who will receive it?

- Is CRISPR safe? Genome editing gets its first FDA scrutiny

I think this is just the bottom of the iceberg for potential therapeutic applications of CRISPR-based systems. For instance, different fusion proteins for epi-genetic editing already have proved their potential, or RNA targeting systems are now enabling more possibilities for flexible targeting of the central dogma. However, the effectiveness can be variable within different contexts and patients. Thus, new paradigms are required to design and enable future CRISPR-based therapeutics for precision medicine applications.

Thanks for reading my story!

Abolfazl (Abe)